On Christmas Day I received an email. It was addressed to my 7-year-old son, and it told him that his coronavirus test was positive.

There were mixed emotions. I was amused at the thought of this strange Christmas present. I was also relieved – ever since his school had closed a day early the previous week because a teacher had tested positive we’d been living with uncertainty. Although a little scary, the knowledge we now had was reassuring.

There was some consternation, of course. When I had swabbed him 4 days previously, I’d kneeled down with my face very close to his open mouth as I tried to tickle his recalcitrant tonsils. Was I now infected? My wife?

I was also curious about his symptoms. He’d said he couldn’t taste his toothpaste, and seemed to be less hungry than usual. That was why I’d decided to order the test that weekend. But apart from those very minor symptoms there was nothing to suggest he’d been ill.

Before Christmas I’d met a friend who had COVID back in March, and was still suffering, 8 months later. Another friend who is a consultant at the local hospital spent 5 days in bed over New Year, not being able to taste anything. Yet my 77-year-old mum, who had to go into hospital for a broken hip, tested positive on discharge and hasn’t had any symptoms.

And when we got my wife tested after the Christmas weekend, it came back negative. She and I both felt a little ‘funny’ about three days after our last London Underground journey in March, so I’m wondering if we’ve been exposed but been fortunate enough to have only very mild symptoms.

Unsurprisingly, there have been genome-wide association studies looking at disease severity. See for example this preprint, ‘Genetic mechanisms of critical illness in Covid-19’. These authors from the University of Edinburgh found at least three genetic loci that seem to be associated with severe disease, including one that encodes antiviral restriction enzyme activators and another in the interferon receptor gene IFNAR2.

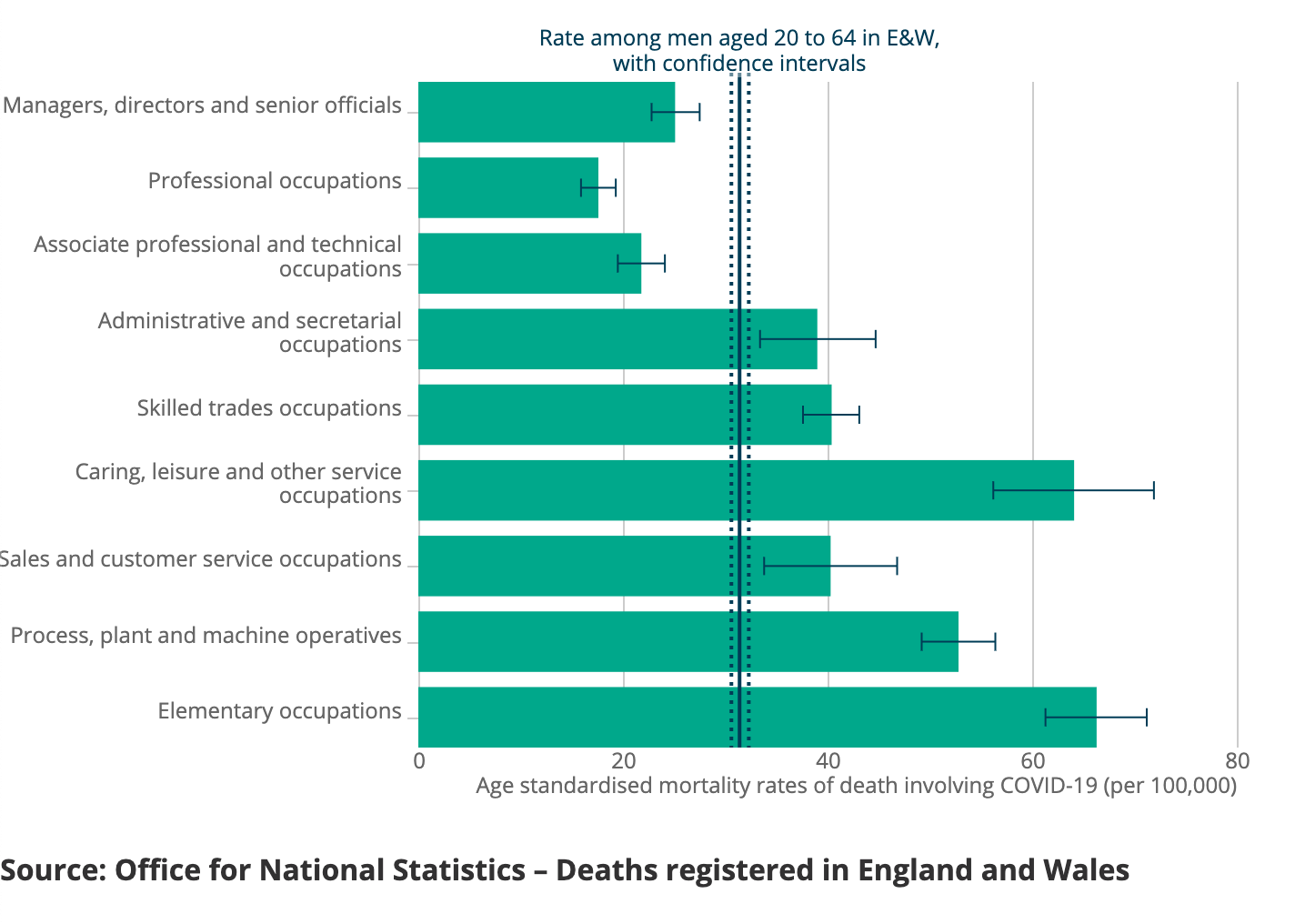

While I would very much like to see if I could get the entire family tested for those loci, there is also an association between occupation and mortality. The type of job you do predicts how likely you are to die from COVID.

According to the Office of National Statistics (ONS), men in elementary occupations (such as labourers and other ‘unskilled’ professions) are twice as likely to die from COVID as working-age men in the general population.

Men in caring, leisure and other service occupations are only just behind this group, while management and professional occupations fare a lot better. Women aren’t as likely to die from COVID as men, but the trends by occupation are similar.

Now, the ONS didn’t adjust for factors such as ethnicity, place of residence or socioeconomic status beyond occupation, so you can’t claim conclusively that differences in levels of occupational exposure to the virus cause different rates of death. But what’s fascinating is that when you look at ‘teaching and educational professionals’, the rates for both sexes are almost half what they are in the population at large.

Teachers get exposed to many different viruses. Any parent of primary school-age children can attest to the cycle of coughs and sniffles that coincides with the new school year. Yet in my experience, teachers are rarely sick, implying that teachers have somehow evolved an immune response that defends them against the onslaught of hundreds of highly mobile fomites every September, while failing to initiate cataclysmic interferon cascades. Perhaps there’s some sort of natural selection going on whereby only those people with perfectly balanced immune systems can make it as teachers.

Anyway, looking deeper into the ONS data at individual teaching occupations, it turns out that a mortality rate can only be calculated reliably for secondary education teachers. And in that subset, the rate is not statistically significantly different from the wider population. Which logically means that the low mortality rate is being driven by tertiary and primary school teachers.

But I’m wondering if we’re not missing an opportunity here to simultaneously maintain some semblance of organized education, relieve the pressure on stressed parents of primary school-aged children, and contribute to the vaccine relief effort.

Imagine: armies of primary school children on extended day trips across the country, carrying little backpacks stuffed with vaccine vials and syringes. Their suitably trained teachers with their invincible immune systems walking door-to-door to deliver vaccinations. The children could learn about the area they’re in and take Maths and English lessons on the fly – and just as importantly, they’re out of their houses and with their friends.

And the vaccine gets delivered to every street in the land.

Worth a shot, no?